My Thoughts On Skip Thoughts

Dec 31 2017 - As part of a project I was working on, I had to read the research paper Skip-Thought Vectors by Kiros et. al with a magnifying glass and also implement it in PyTorch. In this process, I learnt quite a lot about why Skip-Thought works so well despite being very straightforward in principle. In this blog, I would like to share what goes behind the scenes in Skip-Thoughts — small things that actually make it work.

My GitHub implementation: https://github.com/sanyam5/skip-thoughts

Prerequisites

This blog assumes basic familiarity with Neural Networks and Back Propagation. If you are not familiar with these terms I strongly suggest first reading about them from online resources.

Basics

If you’ve already read the Skip-Thoughts paper you may skip this part.

Q. So, what the hell is this Skip-Thought or Thought Vector thingy?

“Skip-Thought Vectors” or simply “Skip-Thoughts” is name given to a simple Neural Networks model for learning fixed length representations of sentences in any Natural Language without any labelled data or supervised learning. The only supervision/training signal Skip-Thoughts uses is the ordering of sentences in a natural language corpus.

Q. Why are fixed size representations of sentences needed?

Fixed representations make it easy to replace any sentence with an equivalent vector of numbers. This makes the process of understanding, acting upon or responding to Natural Language mathematically straightforward. Some examples of such tasks are

- the task of telling whether two sentences are semantically similar in meaning.

- the task of classifying whether a given statement is positive or negative.

One strategy is to learn fixed length representations of individual words as done in Word2Vec. One famous result from Word2Vec is the following:

[king] -[man] +[woman] ≃ [queen]

where [x] represents the vector representation of the word x. But the order of words in the sentence matters as well — “Ram hit Shyam” and “Shyam hit Ram” are two different sentences. Just having word representations of the constituent words leaves the problem of making sense of the order to the user.

A better way is to have a Neural Network also take care of the order of words in a complete sentence which is exactly what Skip-Thoughts does. But, why stop at sentences? Why not parse complete paragraphs or documents? True, parsing complete paragraphs could generate even better representations. But in Skip-Thoughts we settle for a middle ground between words and paragraphs.

Model

Skip-Thoughts model has three parts:-

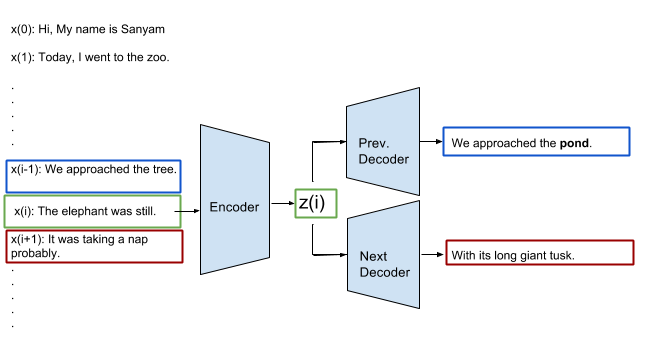

Skip Thoughts model overview

Skip-Thoughts model has three parts:-

-

Encoder Network: Takes the sentence x(i) at index i and generates a fixed length representation z(i). This is a recurrent network (generally GRU or LSTM) that takes the words in a sentence sequentially.

-

Previous Decoder Network: Takes the embedding z(i) and “tries” to generate the sentence x(i-1). This also is a recurrent network (generally GRU or LSTM) that generates the sentence sequentially.

-

Next Decoder Network: Takes the embedding z(i) and “tries” to generate the sentence x(i+1). Again a recurrent network similar to the Previous Decoder Network.

Q. How is it trained?

Skip-Thoughts uses the order of the sentences to “self-supervise” itself. The underlying assumption here is that whatever, in the content of a sentence, leads to a better reconstruction of the neighbouring sentences is also the essence of the sentence.

The decoders are trained to minimise the reconstruction error of the previous and the next sentences given the embedding z(i). This reconstruction error is back-propagated to the Encoder which now has a “motivation” to pack as much information about sentence x(i) that will help the Decoders minimise the error in generating the previous and next sentences.

Q. What does it learn?

The end product of Skip-Thoughts is the Encoder. The Decoders are thrown away after training. The trained encoder can then be used to generate fixed length representations of sentences which can be used for several downstream tasks such as sentiment classification, semantic similarity, etc.

The representations of semantically similar sentences are closer. For example, the representation of 1) “he ran his hand inside his coat , double-checking that the unopened letter was still there” AND 2) “he slipped his hand between his coat and his shirt , where the folded copies lay in a brown envelope” are very close by.

Seems convincing, right? Well, not so fast…

A teeny-tiny problem

The Encoder is just fine but the Decoder has been assigned a herculean task. Consider this:-

Given any sentence it very hard even for a human to tell the sentences, word for word, that can occur before or after that. Try, for example, the sentence “I opened the door”. The possibilities that can precede and succeed this sentence are enormous. Also, sentences similar in meaning such as “We went to the market” and “We went for shopping” are not treated same. The Skip-Thought Decoder is tasked with predicting the exact sentence word for word. So, if a human finds this tough, how is it possible for Skip-Thoughts to predict the neighbouring sentences? How is this even a valid training signal?

Take a moment to convince yourself of difficulty of predicting exactly the neighbouring sentences because understanding what follows depends on it.

Taking a closer look at the Decoder

Let’s take a closer look at the model and try to understand why Skip-Thought works.

Again, Skip-Thoughts Encoder is plain and simple. But the Decoders are a bit tricky. There are two key factors at play here.

-

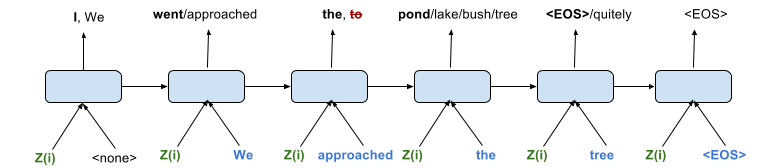

Teacher forcing:- The Decoders generate the sentence word-by-word while being fed the words of the true target sentence from the corpus with a delay of one time-step (see figure below). The teacher forcing is done for 100% of the words being predicted.

-

The prediction is a probability distribution over words that could occur at that position given the context z(i) of a neighbouring sentence and the sequence of words that occurred before the current position.

Unrolling the Decoder in time: The input to the Decoder at every time-step is the Z(i) embedding from the Encoder (in green), the actual words in the target sentence (in blue), the previous hidden state. The output is a distribution over the possibilities of words. In the third time-step, it becomes easy for the Decoder to output “the” instead of “to” as it knows for a fact that the actual word preceding it is “approached” and not “went”.

Training now becomes easy. Decoding is guided not only by the context of z(i) but also by actual words in the target sentence which convey both the grammatical and semantic cues to the Decoder as it generates the target sequentially.

Q. But why 100% teacher forcing? Will that not lead to poor generalisation?

It’s not immediately clear to the reader the reason for supplying true previous words at every time-step. Generally when RNNs are trained for sequence prediction they are randomly (with some probability split) given either i) the true previous label and ii) their own predicted label. Giving RNNs their own predicted labels as feedback helps them generalise better at predicting sequences at inference time (since there are no “true” labels at inference time). There are two possible explanations for why Skip-Thoughts doesn’t used reduced levels of teacher forcing:

Naive Explanation: Since we are anyways going throw away Decoders we don’t care for the performance at inference time we don’t need to reduce teacher forcing.

Better Explanation: Teacher forcing was never meant for producing sequences of words. It exists only as a means for facilitating better word-level predictions by providing the information of preceding words from the true sentences. So reducing teacher forcing is not a matter of choice or inconvenience. Reducing teacher forcing will reduce accuracy.

In the next section I will further motivate why the second explanation makes more sense.

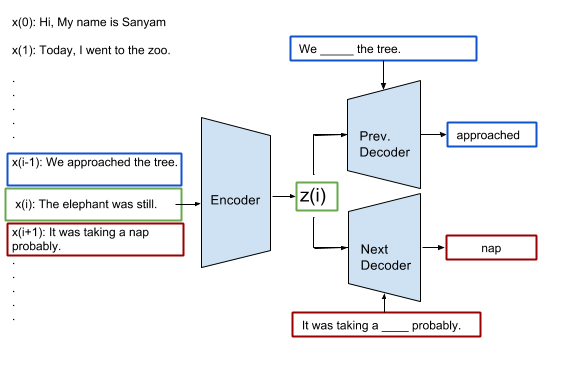

Comparison with Imputation of missing words from sentences

Let’s modify the model a bit. We will predict just one missing word (can be any word) of the next (or previous) sentences given i) the context z(i) of current sentence and ii) the sequence of words and location of the blank (signifying the missing word) in the next (or previous) sentence. See the model architecture below for clarity.

Imputation: Guessing the missing words given all other words and the context of a neighbouring sentence

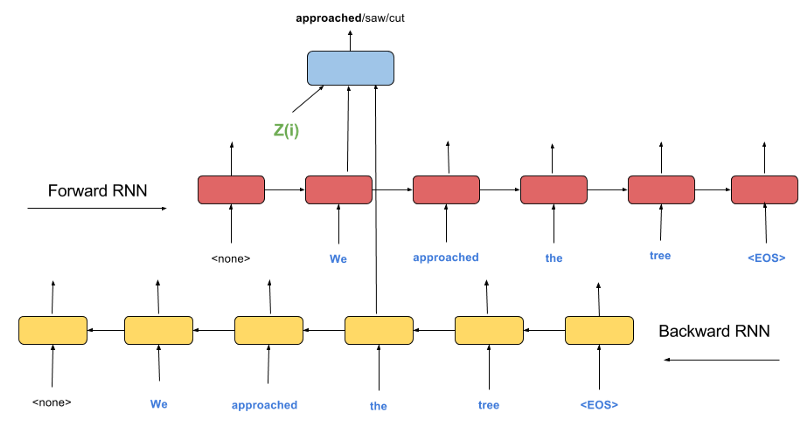

One sensible way to provide all but one element of sequence is by using a bidirectional RNN. The forward RNN captures all words before the blank and a backward RNN captures all words after the blank.

-

Why RNNs? Because they are well suited for variable length sequences. CNNs disregard ordering.

-

Why two RNNs? It is possible to use just one RNN and provide the complete sentence with a fill_this_blank token at the blank position. But a more natural choice is having a forward and backward RNN.

One possible design of the decoder is as follows.

Imputing the missing word: Decoder model

Notice something? If we remove the Backward RNN from this model it becomes essentially the same as the Decoder of Skip-Thoughts model. What seemed like 100% teacher forcing in Skip-Thoughts was actually an half-way measure to what it was truly trying to achieve — Imputation of missing words in the neighboring sentences.

Alternate designs for Decoder

Based on our insight that Skip-Thoughts is just half-way to the Imputation of Missing Words model, we can claim that whatever works for Imputation Decoders will also work for Skip-Thoughts Decoders. This means one could easily use CNNs (for getting the context for previous/next k words) for Decoding.

Q. Why does the Skip-Thoughts not use a Backward RNN?

Using a Backward RNN would clearly increase accuracy and it is unclear to me why it was not used in the first place. I do not know a concrete answer to that but my guess is that using a Backward RNN would make generating sentences impossible using the Decoders. But there are two counters to this explaination:-

-

One can always separately train a one-way Decoder (with just a Forward RNN) after the Encoder has been trained using a Bidirectional Decoder (with both Forward and Backward RNN).

-

Skip-Thought burnt the bridge of generating coherent sentences the moment it used 100% teacher forcing. This means generating sentences was probably not that important. Not sure on this one, though.

Final thoughts

Q. What do the decoders actually learn then?

TL;DR: The decoders learn to fill missing words from sentences given neighbouring sentences.

Both decoders learn primarily two things. First, the grammar. For example knowing that “approached” is not followed by “to”. Learning grammar helps the Decoders avoid grammatical mistakes in an otherwise semantically similar sentence. Second, distribution over words at position p given i) the context z(i) of a neighbouring sentence and ii) the words x(i)[0:p] occurring before the position p (0-indexed).

Q. What does the encoder learn?

The Encoder learns to extract and pack the information in a sentence that helps decoder better predict the words of the previous/next sentences.

It is amazing, at least to me, that this information indeed captures some semantics of the sentences as indicated by admirable accuracy on several downstream NLP tasks such as semantic similarity, sentiment classification, etc.

— — — —

Thank You!

Do checkout my implementation at GitHub: https://github.com/sanyam5/skip-thoughts

Please leave comments below. I would love to hear your thoughts on why you think Skip-Thoughts work. Also, let me know if I missed something.